Today’s distillers pay homage to the past. But they aren’t afraid to tweak the age-old art and science behind great whiskey. Case in point: Yeast research.

Yeast is a basic component of all fermented beverages (beer, wine and spirits). Its function is to convert sugars from grains, plants and fruits into ethanol and carbon dioxide. For years, makers of spirits and other beverage alcohols have used strains from a species of yeast called Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Cerevisiae is preferred for its ability to repress wild microorganisms and efficiently convert sugars, producing consistent alcohol without ‘off’ flavors.

Yeast influences flavor via congeners, which are chemical components produced during fermentation. Distillers have learned that congeners from different yeast strains create different flavor profiles, so it’s not surprising they are experimenting with different strains to arrive at unique or interesting congeners.

Another area for experimentation with yeast is “mixed fermentation,” which combines more than one strain during fermentation. This is an interesting and challenging approach because each individual strain is positive or negative for a particular characteristic, and that characteristic may be desirable. Or undesirable.

Some distillers are experimenting with unique yeast sources such as wild yeast and bacteria. Peggy Noe Stevens writes in American Whiskey (February 25, 2019): “There are stories of taking samples from old pipes or vintage bottles to reproduce a new yeast strain and it not only makes for a great story, but it can be true.”

Wild yeasts are an interesting part of the whiskey story. Like many stories, however, they can become a cautionary tale. MGP’s Ray Furman, fermentation and yeast manager and Master Distiller, notes that distillers should use caution in introducing wild yeasts. They don’t produce alcohol efficiently, which reduces output. Even worse, they create acids and other undesirable congeners that result in “off” flavors. It’s difficult to overcome these negative flavors even with the additional processes of distilling and aging.

Ray notes that wild yeasts are naturally present, but their ability to produce harmful bacteria is reduced with the use of carefully controlled temperature and PH levels.

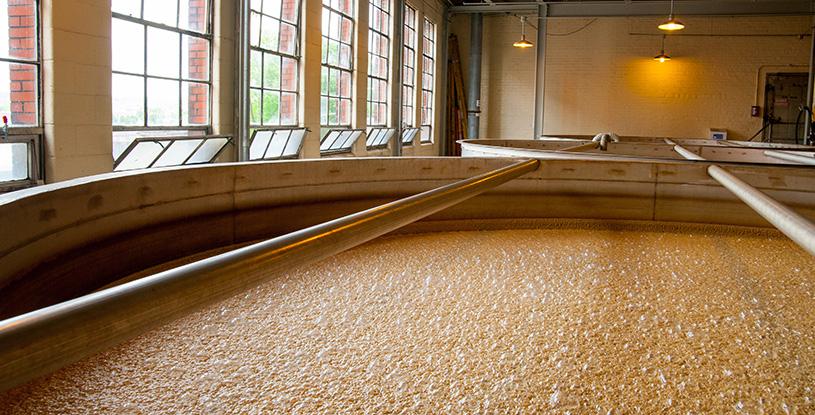

In addition to monitoring every aspect of the fermentation process, Ray spends time in the laboratory experimenting with distillers’ yeasts. His work in the Lawrenceburg, Indiana, distillery draws on a rich heritage of innovation that created a legacy yeast strain.

Fifty years ago, the distillery’s then-owner Seagram’s undertook extensive research into yeast strains. With the help of more than a dozen chemists from the University of Indiana, their study examined 300 strains to determine which offered the best congener profiles (in particular those that did not produce ‘off’ flavors.) The study ultimately identified five, best used for five types of spirits: rye whiskey, wheat whiskey, light whiskey, gin and vodka.

While their research is unlikely to occur at similar scale, today’s distillers are using their spirit of innovation to identify new yeasts and new uses for yeasts to make great whiskeys. We raise our glass to that.